MATI Member Spotlight: Meet Max Zalewski

Max Zalewski translates from Arabic, Spanish and Portuguese into English. He holds a Master’s Degree in Hispano-Arabic Literature from the University of Granada, a Certificate in Arabic into English Legal Translation from the American University in Cairo, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Spanish Literature from the University of Wisconsin. Max has been a MATI member since August of 2014.

Max Zalewski translates from Arabic, Spanish and Portuguese into English. He holds a Master’s Degree in Hispano-Arabic Literature from the University of Granada, a Certificate in Arabic into English Legal Translation from the American University in Cairo, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Spanish Literature from the University of Wisconsin. Max has been a MATI member since August of 2014.

Where do you live and/or work?

Currently I live part of the year in Madison, WI and part in Granada, Spain. In Madison, I work from home, coffee shops, a co-working space and the UW-Madison libraries; in Granada, I work from home, the Escuela de Estudios Árabes in Albaycin, the University of Granada library, and if I am working on projects that do not require internet, I will often venture up to the mountains behind the Hermitage of San Miguel. The view from there is mesmerizing: from Sacromonte, the Valparaiso extends to the left, the Alhambra and Generalife are perched on top of the Sabika Mountain in the center, and the Vega extends into the distance to the right. Being surrounded by such serene scenery may sound distracting, but conversely, it is here where I find the most clarity.

How did you acquire your B language(s)?

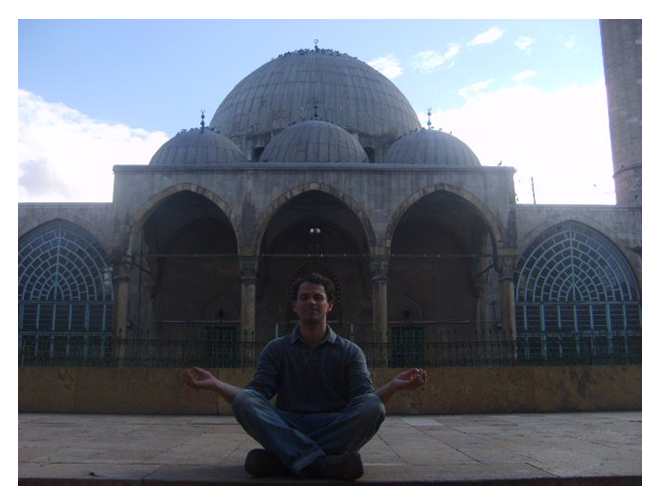

I started learning Spanish in Grade School and subsequently travelled to Nicaragua in High School for a summer immersion program. That trip infected me with the proverbial travel bug and I have had my eyes set on the horizon ever since. While majoring in Spanish at UW, I took several Portuguese and Arabic classes and studied abroad for one year in Madrid. After graduating, I moved to Damascus to continue learning Arabic and supported myself by translating Spanish and Portuguese. I quickly fell in love with the lifestyle of living abroad, working as a translator and learning a new language. In addition to Damascus, I have spent the last 5 years living in Barcelona, Aleppo, Madison, Cairo and Granada.

Do you have a book, blog or methodology that you would like to recommend?

I love reading fiction and highly recommend La Alhambra de Salomón, written by José Luis Serrano. It is a historical fiction that revolves around the life of Samuel Nagrela, the most prominent Jew in Al-Andalus. There is a theory that the Alhambra was initially designed to replicate the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem in order to create a Solomonic Republic in Granada. This novel explores this theory, and perhaps most interestingly, Serrano invents female characters who earn the respect of men through their intellect, including Ilbia, a fictional character to whom he attributes the original architectural design of the Alhambra. José Luis, his agents and I are working to get my translation published in English, but as yet it is only available in Spanish. It is an excellent read for anyone interested in Jewish history, the romantic history of Al-Andalus, the enigmatic tale of the Alhambra, as well as the untold stories of the women of yesteryear.

Where do you see your field going in the future?

What are the most urgent issues to be addressed? I find it fascinating that we don’t have a way to quantitatively measure the quality of translation. People have been writing about translation theory for millennia and yet our industry still has no consensus about what translation is. The ATA has a magic grading scale, but how many times has a client, writer or publishing house ever used that as a reference for measuring the quality of a translation you’ve done? For me, never. Poof!

I think it is possible to quantitatively measure language and perception by measuring brain waves. It seems to me that the goal of the translator should be creating the same average perception for the target audience as the original average perception of the source audience. Naturally, this has its challenges. What is an average perception? How do perceptions of texts change over time? Are all perceptions possible to create in every language or are some inherent to the languages themselves? The argument over whether or not to favor the author or the reader in the face of linguistic barriers needs to take a step forward and explore the essence of the translator’s task: creating access to a set of perceptions to an audience that is otherwise capable to accessing these perceptions. In the future, I see our field increasingly incorporating science into the art of translation. Machine translations already have their place in the market, but poetry and literature will be the last to use machines because they are significantly more open to human interpretation. By mapping the brain’s perception of language across cultures, I believe it will lead us to a clearer understanding of what each language’s limitations are and what we can do as translators to overcome these barriers.